(Abundance series #3)

Ideas can help break an accelerating downward spiral of polarization by offering inspiration – but to be credible, a positive vision also needs to be accompanied by a practical agenda for action. Ezra Klein & Derek Thompson’s best-selling book, Abundance offers a compelling positive vision along with a sharp wake-up call for progressive governance. But it largely leaves unresolved how that vision can become a strategy for action.

This post explores that question through three linked mini- case studies which focus on one central dimension of problem-focused coalitional governance: how civil society engages at the level of concrete problems – and how different modes of engagement shape outcomes. The three cases are:

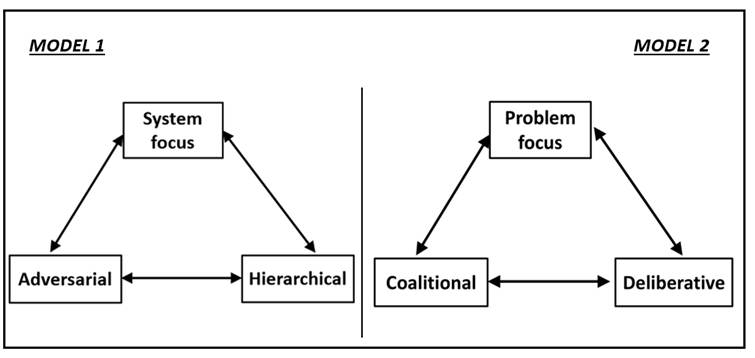

- Mini-case study #1 explores how ongoing, adaptive engagement by civil society has been key to South Africa’s reversal of a disastrous HIV/AIDS pandemic – a decade-long high-profile adversarial campaign was followed by sustained efforts to work more coalitionally with reformers within government to help strengthen both policymaking and implementation.

- Mini-case study #2 explores how problem-focused coalitional governance helped improve learning outcomes in a half-dozen countries, even in the face of broader governance messiness.

- Mini-case study #3 explores how a disproportionate emphasis on hierarchical, arms-length and adversarial modes of engagement has constrained national, subnational and school-level efforts to improve learning outcomes in South Africa.

The mini-case studies draw on a chapter, co-authored with long-time civil society activist Mark Heywood, in a just-published book, The State of the South African State, plus a decade of prior comparative research on the political economy of education sector reform.

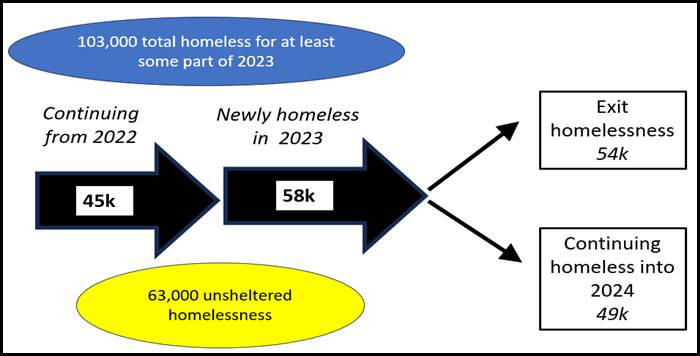

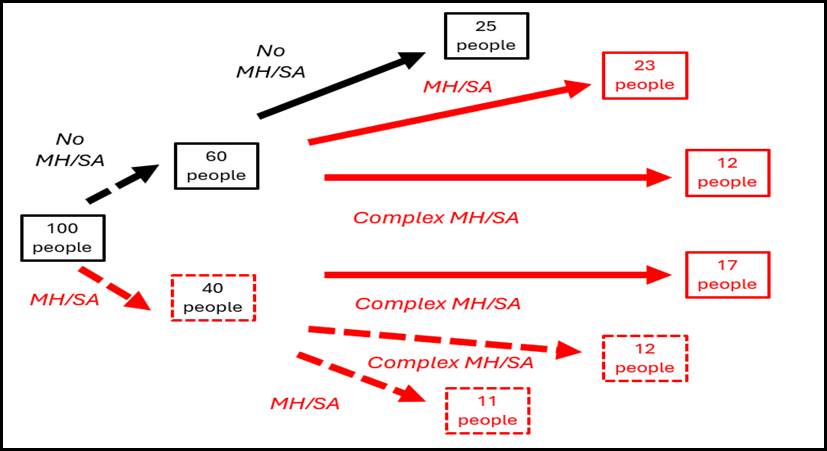

Together with two companion essays, this piece forms part of a short series that probes how to close the gap between vision and action. A stage-setting post situates Abundance within the larger arc of literature on political orders, and highlights both the book’s positive vision and its critique of progressive governance. A companion conceptual post (see here) lays out a framework centered around the collective efforts of coalitions of reform-oriented public officials and non-governmental actors to address concrete problems. (A fourth post, forthcoming in January, will be a stocktaking and update of Los Angeles’ efforts to address homelessness in the face of a a worsening fiscal crisis. (See here for some of my recent research on both LA’s crisis and recent governance reforms aimed at addressing it.)

****

Mini case study #1: South Africa’s HIV-AIDS Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) (Click here for access to the Levy-Heywood case study; Heywood has played a leadership role in the TAC since its inception.)

The TAC is an extraordinary example of successful activism on the part of civil society: “Upon the TAC’s formation in 1998, no person living with AIDS was receiving life-saving antiretroviral treatment in the public health sector and almost all infected people died….. [A decade later, South Africa began to roll out what has become….] the largest HIV treatment program in the world, now covering over 5.8 million people and nearly 80 per cent of the eight million people living with HIV in South Africa. Perhaps the most dramatic evidence of this programs results has been a rise in life expectancy of more than a decade for men and women and a massive drop in infant mortality due to HIV infection.”

The case study explores the interplay between adversarial and coalitional strategies over the TAC’s quarter century of effort: “The TAC’s history can be divided into two parts: a period of confrontation over government policy and President Mbeki’s AIDS denialism (1998–2007); and a coalitional period (and when deemed necessary, confrontation and/or challenge), working with committed public officials over implementation of a policy that TAC eventually managed to co-create with the government (2007 to the present).”

The first period was characterized by: “….almost a decade of intense conflict between TAC and the government over its policy, particularly its refusal to include a treatment component to HIV prevention and care….This first period was bitter and divisive……

Eventually, government responded to pressure from the TAC (and broader disquiet , including from within the ANC, with the prevailing policies): In late 2006/7, the TAC delegated several of its leaders to work with the Office of the Deputy President to develop a new framework for a National Strategic Plan on HIV….agreement was reached in early 2007….. Key TAC leaders were appointed to senior positions in the South African National AIDS Council, SANAC (a body that had been set up by President Mbeki in 1999), where they worked closely with government. For a period SANAC became a forum for de facto co-governance of the AIDS response.

From 2007 onwards, there was a far-reaching transformation in how government and civil society engaged with each other: “The TAC offered public servants in the Health Department a vision of care and treatment that provided hope, encouraged innovation and inspired (rather than commanded) performance…… Through its branches, TAC assessed the actual state of delivery on the ground and frequently allied with local health workers. It was central to setting up organizations like the Stop Stockouts Project which monitors the availability of essential healthcare medicines and children’s vaccines…..The TAC tackled the serious stigma that surrounds HIV infection by building hundreds of branches for people living with HIV. Its branches were conduits for its pioneering program of ‘treatment literacy’ carried out with the guidance and support of health professionals.”

South Africa’s approach to addressing HIV-AIDS had shifted from accelerating disaster to an exemplar of what coalitional, learning-oriented and deliberative governance can achieve – a ‘best practice’ case that paralleled the primary health care reforms in the Brazilian state of Ceara, documented by Judith Tendler in her classic book, Good Government in the Tropics. (Note, though that, as mini-case-study #3 will explore further, an embrace of coalitional engagement has been more the exception than the rule in democratic South Africa.)

****

Mini case study #2: improving learning outcomes in middle income countries.

The second mini-case study draws on a synthesis of a dozen country studies of the politics of education policy reform and implementation written for the Research Programme on Improving Systems of Education (RISE). What follows highlights some striking (and paradoxical when considered through a conventional lens) findings on how problem-focused coalitional governance added value at each of national, provincial, district and school levels.

At national level:

A comparison of the case studies of education sector governance in Chile and Peru points to both some limitations of top-down governance, and some strengths of problem-focused coalitions. In Chile, interactions among stakeholders largely were top-down and systematically managed, yet improvements in learning outcomes were modest. By contrast,Peru achieved large gains in learning outcomes, even though it has long had to navigate an extraordinarily turbulent political and institutional environment – including an education sector led by 20 ministers in 25 years. As the Peru country case study explored in depth, Peru’s messier, less formalistic and more iterative process of policy formulation and adaptation helped build broad legitimacy among stakeholders:

“ Civil society organizations – NGOs, universities, think tanks and research centers – have also played a key role in defining policy agendas [and….] in the development of education policies and reforms. Though agreements are often ignored by ministerial administrations and political parties, they have certainly contributed to the continuity of agendas and to the advancement, through piecemeal, of reforms.”

At provincial level

In his award-winning 2022 book, Making Bureaucracy Work: Norms, Education and Public Service Delivery in Rural India Akshay Mangla distinguishes conceptually between legalistic and deliberative bureaucracies, and analyzes the strengths and weakness of each in improving learning outcomes in two Indian states:

“Legalistic bureaucracy in Uttar Pradesh has promoted gains in primary school enrollment and infrastructure…. enabling officials to resist political interference when providing inputs to schools…..[But] local administration’s adherence to rules imposed administrative burdens…. Cumulatively, these processes contributed to low quality education….”

By contrast, in Himachal Pradesh, deliberative norms and participatory/coalitional governance have been mutually reinforcing. “At independence, Himachal Pradesh was among India’s least literate states…. HP is now among India’s leading states with respect to literacy and primary education policy education indicators….. Deliberative bureaucracy is found to have made a decisive impact… enabling state officials to undertake complex tasks, co-ordinate with society and adapt policies to local needs, yielding higher quality education services.”

At district level.

Ghana and Bangladesh illustrate how local coalitions helped improve learning outcomes, even in the face of broader systemic weaknesses. In Ghana, interactions between decentralization and clientelism added to the incoherence and politicisation of the education sector. But there was a silver lining: “The drivers of improved performance and accountability do not flow from the national to the local level, but instead have to be regenerated at the level of districts and schools…. In [some] districts…. there was evidence of the emergence of a developmental coalition between community, school and district-level actors….including ‘political officials and teacher unions…..evident at district level, and mirrored at the community level.”

Similarly: “Bangladesh features an education system which, while formally highly centralized, is in practice fairly decentralized and discretionary in whether and how it implements reforms….. Learning reforms were adopted and implemented to the extent that the relationship between school authorities, the local elites involved in school governance, and the wider community aligned behind improved teacher and student performance.”

At school level

Kenya’s long history of involving parents and communities in the governance of schools has had far-reaching consequences. As a long-standing observer of the system reported: “What one sees is an expectation for kids to learn and be able to have basic skills…. Exam results are…. posted in every school and over time so that trends can be seen. Head teachers are held accountable for those results to the extent of being paraded around the community if they did well or literally ban from school and kicked out of the community if they did badly.”

****

Mini case study #3: South Africa’s fraught efforts to improve learning outcomes.

Notwithstanding the encouraging examples in mini-case-study #2, many education systems seem stuck in low-level equilibria, with repeated fruitless attempts to improve poor learning outcomes by doubling down on top-down, legalistic reforms. Heywood and Levy’s second case study (which draws on Levy et. al, 2018) explores the balance between adversarial/legalistic and coalitional/deliberative approaches at each of national, provincial and school-levels.

At national-level: “South Africa’s education sector stakeholders (inside and outside of government) have failed to co-operate sufficiently to be able to bring about effective change. Part of the reason for this failure can be traced to more general societal pre-occupations with adversarial civil society approaches and bureaucratic insulation. [Examples include]:

- A failure among experts to constructively work through their disagreements has been an important part of why the country has repeatedly failed to put in place any systematic assessments of learning before the end of twelfth grade……

- South African Democratic Teachers Union (SADTU) has almost uniformly been demonized by sector professionals, media and many politicians as disruptive and as a principal cause of the sector’s failures even though, as with teachers’ unions everywhere, SADTU has to navigate inherent tensions between its role as an advocate of the material interests of teachers and its role as a professional organization. Coalitional approaches would include efforts to build common cause with teachers committed to the more professional parts of this dual identity….”

At subnational-level: “Civil society’s default mode of engagement at provincial level often has been adversarial. Yet judicial victories and resulting court-imposed obligations to improve infrastructure have limited potential for impact [in those provinces] where bureaucracies lack the legalistic/logistical capacity for follow-through.”

At school-level: The 1996 South African Schools Act (SASA) included reforms that gave far-reaching authority to school governing bodies in which parents were the majority. These reforms were motivated in part by the liberatory impulses of grass-roots democratic movements, and in part by the concerns of apartheid-era elites about how schools would be governed. The latter has enabled public schools serving (now more multi-racial) elites to perform well. By contrast:

“While a few exemplary civil society organizations work collaboratively at school and community levels, there has been little sustained effort to breathe life into the SASA architecture within low-income communities….. We [Heywood and Levy] recognize that, outside elite settings, it can be difficult for parents and communities to exercise their voices…but it is not the practical challenges facing civil society that account for the lack of attention paid to the possibilities for inclusive governance created by SASA. Rather, it is the ideational lens through which South Africans approach the role of civil society in public service provision.”

****

As the mixed response to Abundance reveals, efforts to translate a positive vision into a practical agenda for change seem repeatedly to become snarled in binary either/or discourses. The reasons seem rooted less in evidence than in competing ideational ‘priors’ – in this instance a ‘high modernist’ perspective that top-down institutional engineering is necessary and sufficient to effect change, versus a ‘social justice’ perspective centered around mobilizing against unjust and corrupt elites.

The case studies in this blog post (and the conceptual framework laid out in a companion post) point towards a hopeful third possibility – namely that bringing attention to the practical can inspire in its focus on concrete gains, in its evocation of human agency, and in the power that comes from cultivating shared (problem-level) purpose to actually get things done. As Heywood & Levy argue, what to prioritize varies by place and time.

Here is how we open our chapter: “Civil society played a key role in the struggle to end apartheid. In the first three decades of South Africa’s democracy, civil society’s continuing efforts to hold government to account have yielded some massive, vital victories. But times have changed……”

Here is how we conclude: “A crucial, continuing challenge for the South African state is to renew a sense of hope and possibility. Highlighting failures and mobilizing around them does not renew hope – on the contrary, it can risk deepening disillusionment. The times call not for deepening confrontation, but for a mode of social mobilization on the part of civil society that fosters, rather than undercuts, a sense of solidarity and shared purpose.”

The above is not relevant only to South Africa. The contemporary USA finds itself trapped in its own downward spiral of disillusionment and polarization. In Abundance, Klein & Thompson offer acounter- vision that is intended to inspire. This, they suggest, will require a state that is both capable and willing to act. But as a vibrant recent literature (synthesized here) has explored, effectiveness alone is not sufficient to renew civic perceptions of the legitimacy of the public domain. n his 2020 book, The Upswing, Robert Putnam sought to draw lessons for the contemporary USA from the 1880s and the 1920s:

A distinct feature of the Progressive Era was the translation of outrage and moral awakening into active citizenship …Progressive Era innovations were seeking to reclaim individuals’ agency and reinvigorate democratic citizenship as the only reliable antidotes to overwhelming anxiety… National leadership came after sustained, widespread citizen engagement….. A [new] upswing will require ‘immense collaboration’, [leveraging] the latent power of collective action not just to protest, but to rebuild.”

Perhaps the ideas and experiences laid out in this blog series can contribute in a small way to setting aside either/or polarities and embracing a similarly inclusive vision of change.