Fueled by hope, I spent the 2010s travelling back-and-forth between South Africa and the USA, sharing an optimistic approach to integrating governance and development strategies with mid-career practitioners at both SAIS and the Mandela School. But the subsequent decade unfolded in unexpectedly toxic ways in both countries. It felt important to complement with-the-grain pragmatism with an exploration of underlying challenges. A 2021 co-authored paper explored why things turned rancid in South Africa. My new paper – How Inequality and Polarization Interact: America’s Challenges Through a South African Lens, also published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace – takes a comparative perspective. This post lays out five personal take-aways from the comparison. (Here’s a link to the paper’s executive summary).

Take-away #1: Far more than is the case for contemporary South Africa, America’s current wounds – increases in inequality since the 1980s, and their attendant social and political correlates – have been self-inflicted.

Back in the 1970s, I had been drawn to the USA by its openness, its commitment to freedom, equal dignity and equal justice for all – everything that the South Africa I left behind was not. With its 1990s ‘rainbow miracle’ transformation from apartheid to constitutional democracy, South Africa became a new beacon of possibility for people around the world who value democratic governance and inclusive societies. However, the country’s subsequent reversals were not wholly unexpected. Three decades after the end of apartheid, South Africa remains among the world’s most unequal countries, and its fraught racial history continues to fester – though the rawness and relative recency of the anti-apartheid struggle perhaps continues to offer some immunization against a further-accelerating downward spiral.

For the United States, however, the converse may be true. In the decades subsequent to World War II, the combination of an equitably growing economy and a vibrant civil rights movement had fostered the hope of deepening economic and social inclusion. But beginning in the 1980s, the benefits of growth became increasingly skewed, and ‘culture wars’ became increasingly virulent. Complacency bred of long stability may have lulled America into political recklessness at the inequality-ethnicity intersection – a recklessness that risks plunging the country into disaster.

Take-away #2: In both South Africa and the USA, the drivers of polarization have been multiple and mutually reinforcing; essentialist explanations that focus narrowly only on a single dimension – economic, institutional, cultural or racial – and ignore the others are, at best, seriously incomplete.

The Carnegie paper distinguishes between polarization’s demand-side and its supply-side. The demand-side comprises the way citizens engage politically – as shaped by power, by their perceptions of the fairness of economic outcomes, and by whether they frame identity in inclusive or in us/them ways. The supply-side comprises political entrepreneurs and the ideas they champion – ideas about how the world works; ideas about identity. Mutually-reinforcing interactions between the demand- and supply-sides can become increasingly toxic – potentially even to the point of a doom loop that destroys constitutional democracy.

Take-away #3: Both South Africa and the USA need to be more pro-active in renewing economic inclusion – but making the shift from an inequality-fueling to an inclusion-supporting economy is less daunting than it might seem.

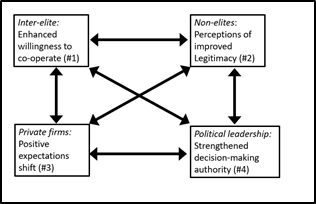

When considered through the lens of the interaction between inequality and ideas, pro-inclusion policies are less important as ends in themselves than for how they affect the willingness of citizens to accept the rules of the game (including the distribution of economic outcomes) as broadly legitimate. As South Africa’s rainbow miracle turnaround in the 1990s and early 2000s shows, a turn from anger to hope does not need a comprehensive package of pro-equity reforms. Rather, reforms that foster “good-enough inclusion”—some immediate gains that signal that things have changed, combined with credible signals that longer-term structural change is underway—can set in motion a virtuous spiral, which can be sustained as long as the momentum of positive policy change continues to unfold over time.

Take-away #4: The influence of economic elites, though often obscured beneath the headlines, has been central in both countries – for both good and ill.

In South Africa, as Alan Hirsch and I explored in depth, South Africa’s business establishment played a leading role in helping to midwife negotiations between the white minority government and the ANC. In the USA, organized business was an important part of the elite consensus that fueled three decades of inclusive economic growth subsequent to World War II. In recent decades however, a segment of the elite has actively financed political entrepreneurs who have skillfully championed a combination of polarizing cultural discourse and distributionally regressive economic policies. This is a classic example of elite capture, a phenomenon familiar to scholars of comparative politics. Paralleling what happened in 1980s South Africa, might America’s economic elites wake up to these risks and become more open to inclusive renewal?

Take-away #5: In settings that are open politically, turnaround will be achieved less by directly engaging polarization’s most toxic champions, than by working around them.

Mass political mobilization was pivotal to South Africa’s shaking loose the shackles of apartheid – and new calls to the barricades might seem to be the obvious response to current political and governmental dysfunction. However, different times and different challenges call for different responses. Currently, both the South African and U.S. governments are, at least aspirationally, committed not to accelerating polarization but to strengthening both inclusion and the institutional foundations of democracy. In such contexts, some compelling research suggests that what is called for is not fighting polarization with more polarization but lowering the temperature by fostering deliberative discourse, focused on positive, hope-evoking options. As happened once before in the USA, the aim would be for a myriad of collaborative, problem-focused grassroots initiatives to serve as potential building blocks for a twenty-first-century social movement– a movement that views cooperation in pursuit of win-win possibilities not as weakness but as key to the sustainability of thriving, open, and inclusive societies.