Ambiguity has its uses – but only up to a point. Its limitations became evident in an early 2016 research retreat to take stock of progress in research on ‘political settlements’. The retreat (sponsored by the Effective States and Inclusive Development research programme) revealed that, beneath a shared, enthusiastic embrace of the transformative potential of political settlements analysis for development practice, were very disparate understandings of the term. Some researchers explored political settlements through the lens of power; others through the lens of institutions; others moved ambiguously between the two.

Work over the subsequent six years has, in my view, decisively resolved the ambiguity. Reflecting the intellectual evolution, this piece explores conceptually how power and institutions interact to shape a variety of distinctive contexts for development policymaking and implementation. A companion blog summarizes how the resulting typology was applied in a recent comparative evaluation of the political economy of education systems and their reform in a dozen countries, prepared for the RISE research programme.

Typologies provide a useful way of drawing sharp distinctions among a small number of heuristic patterns that, considered together, delineate a variety of contexts along which many real world polities might be aligned. My 2014 book Working with the Grain built a typology around cross-country variations in institutional characteristics. The typology laid out in the 2022 book Political Settlements and Development: Theory, Evidence, Implications gives primacy to variations in the configuration of power. (The book was a multi-author effort led by Tim Kelsall; I was one of the co-authors.) This piece integrates the two approaches, using the four variables included in Figure 1.

Kelsall et. al’s definition of a political settlement provides a useful point of departure for clarifying the relationship between power and institutions. It defines a settlement as:

“An ongoing agreement (or acquiescence) among a society’s most powerful groups over a set of political and economic institutions expected to generate for them a minimally acceptable level of benefits, which thereby ends or prevents generalized civil war and/or political and economic disorder”

While both power and institutions feature in the above definition – a settlement is reached when powerful groups agree on the ‘rules of the game’ (i.e. the institutions) that govern the settlement – the 2022 book focuses principally on the delineation of power, and its consequences. It carefully defines two aspects of power:

- The social foundation (SF) characterizes who is powerful – the included socially salient groups (insiders, groups to which policy must somehow respond) as opposed to the excluded (outsiders)…along a spectrum that extends from broad (nearly all social salient groups belong) to narrow (most are excluded).

- The concentration of power (PC) characterizes the extent of power – the extent of coherence in the allocation of decision-making procedures and authority among insiders, ranging from concentrated (highly coherent) to dispersed (lacking in coherence).

The book reports measures of each of PC and SF over time in forty-two countries in the global South, and uses these measures to explore statistically the causal influence of each on development. Higher levels of PC turn out to be associated with more rapid economic growth, and higher levels of SF with broad-based gains in social indicators.

Considering SF and PC from a more disaggregated perspective yields additional insights. The SF variable underscores the importance for inclusive growth of empowering excluded actors– both at an aggregate level and at more micro-levels by giving ‘voice’ to beneficiaries who are intended to benefit from social programs. The PC variable directs attention to the roles of three sets of drivers – distributional, ideational and institutional – in shaping the balance between co-operation and conflict in a country’s polity:

- Distributional drivers. As per the definition of a political settlement, a necessary condition for a high PC (and thus rapid growth) is that the breadth of the SF and the distribution of economic benefits are aligned with each other. (Note that both broad SF/inclusive growth and narrow SF/unequal growth are consistent with this condition, at least in the short-to-medium term.) A loss of alignment between the distribution of power and of economic benefits is likely to result in a decline in PC, with an associated slowdown in economic growth, and rise in political polarization. (See here and here.)

- Ideational drivers. As the 2022 book details (building on Ferguson 2020) political settlements can usefully be understood through the lens of collective action. Shared ideas can provide a basis for achieving co-operative outcomes to mixed-motive bargaining challenges (and thus a high PC); ideational political entrepreneurs (populist or otherwise) can destabilize a previously stable settlement. (See here and here.)

- Institutional drivers. As per the definition of a political settlement, institutions (‘the rules of the game’) provide the container for a political settlement. The institutional arrangements can take a variety of distinct forms, each of which shapes interactions among stakeholders in a distinctive way. Attention to institutions is thus key to addressing a central question confronting practitioners: Given the incentives and constraints prevailing in a specific context, what might be some tractable, context-aligned entry points for improving development outcomes?

This last question brings us to the two institutional variables identified in Figure 1.

Variable #3 in Figure 1 can usefully be interpreted as a continuum between wholly top-down (principal-agent) governance and peer-to-peer governance among multiple principals. As its location at the power-institutions intersection in Figure 1 suggests, this continuum can be interpreted both from the perspective of institutions and of power:

- As institutions, both principal-agent and multi-principal governance have been the focus of a voluminous literature (for example here, here, and here).

- As power, each depicts a very different relationship among stakeholders – unequal power in the former, and interactions among relative equals in the latter. At all levels – from the micro (families; firms) to the meso (communities) to the national – horizontal governance between peers plays out very differently than hierarchical governance arrangements that link those who are powerful with those who are not.

As variable #3 suggests, high PC can thus be achieved via two distinct institutional forms – top-down, hierarchical command-and-control, or peer-to-peer resolution of horizontal challenges of collective action.

Variable #4 distinguishes among institutions according to and whether the rules of the game take the form of personized deals or impersonal rules. This distinction is given only limited attention in analyses of power (including the 2022 volume), but it is central to the contributions of Douglass North and colleagues (see here, here and here), yet. As North and colleagues argue persuasively, impersonal institutions cannot be created by fiat; they emerge as a facet of long-run processes of political, economic and social changes.

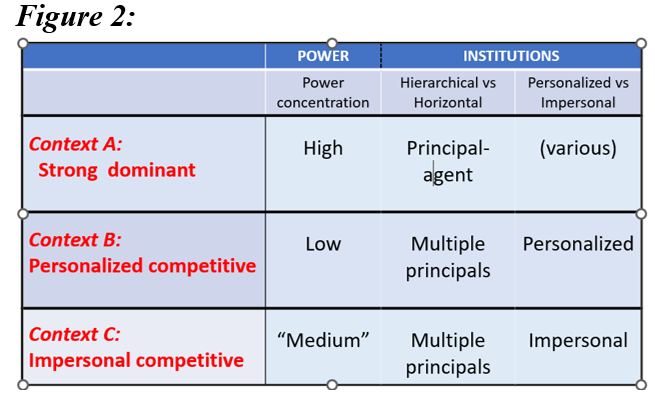

Considered together, variables #2, #3 and #4 provide the basis for a typology that distinguishes among a variety of political settlements, each with distinct institutional forms, and thus distinct, context-aligned entry points for improving development outcomes. Logically, with three variables, each aligned along a continuum, the number of possible types is large. The goal, though is not comprehensiveness, but to focus attention on a few core contexts – radically different from each other, each resonant with a familiar ‘real-world’ pattern, and each characterized by distinctive patterns of incentive and constraint, and thus distinctive entry points for improving outcomes. Figure 2 below identifies three types that meet these criteria. (In applying this framework, I have found that many countries can be interpreted as hybrid combinations of the three – but I have not come upon a fourth type that meets the tests of both real-world resonance and enough qualitative distinctiveness that it warrants inclusion as an additional category.) The paragraphs that follow elaborate on each of the types, drawing on the companion blog on education systems to signal their practical relevance.

In context A (strong dominance), power is highly concentrated, and exercised top-down – with all of the strengths of decisiveness, and the pathologies of hubris and demotivation of subordinates that can accompany this institutional mode of exercising power. The political economy of education case studies for Indonesia, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Tanzania and Vietnam illustrate some of the ways in which dominance plays out in practice. As the education research details, key to achieving gains in these contexts is to engage top-level leadership around purposes.

Context B (personalized competition) is characterized by fragmented authority: multiple centers of power, limited capacity for co-operation, and limited compliance with formal rules (including the rules necessary for the functioning of a formal bureaucracy). In this context, as education case studies for Bangladesh, Ghana, Kenya and South Africa’s Eastern Cape province illustrate – and as a broader literature has explored in depth (see here, here and here) – entry points for achieving gains come not from efforts at systems reform, but from more focused efforts to strengthen islands/pockets of effectiveness.

Context C (impersonal competition) is characterized by strong formal ‘rules of the game’ intended to provide a platform both for resolving conflict among stakeholders and their goals, and for implementation. In successful, mature democracies this platform can indeed result in a shared commitment among powerful interests to craft win-win resolutions of collective action problems, and in the effective operation of public bureaucracy. However, as the education case studies of Chile, Peru, India and South Africa illustrate, the all-too-common result is instead a combination of unresolved political contestation over goals (and thus, as per Figure 2, a ‘medium-level of PC), exaggerated rule compliance and/or performative isomorphic mimicry.

More broadly, as many democracies (even seemingly mature ones) are demonstrating, polarized discourse renders impersonal competitive contexts increasingly vulnerable to a cumulative delegitimization of the public domain, and a downward spiral of institutional decay. Reversing downward spirals is a central challenge of our time. At a micro/sectoral level, as I summarize in the companion blog, the education studies offer some interesting insights as to how this might be achieved across the different contexts. At a broader level, I explored some possibilities in a comparative analysis of interactions between inequality and polarization in South Africa and the United States. Extending this analysis into a broader exploration of what it will take to turn from rage to renewal will be a central focus of my work going forward.

I’ve been puzzling (yet again!) over the usefulness of anti-corruption as an entry point for engagement by civil society, donors and other developmental champions. Always and everywhere, behaving ethically is surely crucial to meet the most important test of all — the “look oneself in the mirror every morning” test. The question for activists is not whether we should model ethical behavior — an obvious “yes” — but what are the pros and cons of an anti-corruption ‘framing’. I list below three analytically strong arguments against using anti-corruption as an entry point– but also one compelling argument for its use. It would be terrific if this post could get some fresh new conversation underway on the dilemma.

I’ve been puzzling (yet again!) over the usefulness of anti-corruption as an entry point for engagement by civil society, donors and other developmental champions. Always and everywhere, behaving ethically is surely crucial to meet the most important test of all — the “look oneself in the mirror every morning” test. The question for activists is not whether we should model ethical behavior — an obvious “yes” — but what are the pros and cons of an anti-corruption ‘framing’. I list below three analytically strong arguments against using anti-corruption as an entry point– but also one compelling argument for its use. It would be terrific if this post could get some fresh new conversation underway on the dilemma.