Even as time becomes shorter and the mood darker, I find it helpful to look beyond the immediacy of crisis and probe the possibilities of renewal. In so doing, I continue to take inspiration from Albert Hirschman’s ‘possibilism’ – the endeavor to “….try to widen the limits of what is perceived to be possible…. and figure out avenues of escape…. in which the inventiveness of history and a ‘passion for the possible’ are admitted as vital actors”. In recent years, I have sought to bring the spirit of possibilism to an exploration of governance at the interface between citizens and the public sector.

A combination of rule-boundedness and insulation of public bureaucracies from day-to-day pressures have long been central tenets of conventional efforts to improve public governance. But conventional efforts have not helped stem a dramatic collapse in recent decades of trust in government and of civic perceptions regarding the legitimacy of the public domains. , As I explored in some earlier work, multiple drivers account for this collapse in trust. Even so, the question of whether the narrowness of mainstream approaches to public sector reform has contributed to the loss of civic trust has continued to nag at me.

Complementing mainstream approaches to public sector reform, might there perhaps be another way forward – one that can both help improve public-sector performance and, of particular import in these times of polarization and demonization of government, do so in a way that helps to renew the legitimacy of the public domain? Might a more ‘socially-embedded’ bureaucracy (SEB) help achieve gains on both the effectiveness and legitimacy fronts? This blog post provides (as a substantial update to an earlier piece) an overview of some of my recently published and ongoing work that addresses these questions.

Exploration of SEB’s possibilities often is met with skepticism. In part, this is because SEB is radically at variance with the mainstream logic of how public bureaucracies should be organized; indeed, as I explore further below, embrace of SEB is not without hazard. But another reason for this skepticism is that SEB is one facet of a broader agenda of research and experimentation that aims to help ‘redemocratize’ the public sector – and enthusiasm among champions of redemocratization has all-too-often outrun both conceptual clarity and empirical evidence. In a generally sympathetic review, Laura Cataldi concludes that much of the discourse proceeds as:

“….an umbrella concept under which a large variety of governance innovations are assigned that may have very little in common……Most of the proposed solutions are situated at the level of principles such as participation, deliberation and co-creation of public value, rather than being concrete tools……[Protagonists] seem to propose models of management, governance and reform that are too abstract, and ultimately lacking in terms of concrete administrative tools…..”

In the work introduced below, I have sought to distil from both the academic literature and the experience of practitioners a set of insights that can help strengthen SEB’s analytical foundation.

I define a ‘socially embedded bureaucracy’ (SEB) as one that incorporates “problem-focused relationships of co-operation between staff within public bureaucracies and stakeholders outside of government, including governance arrangements that support such co-operation.” Questions concerning the value of SEB arise at both the micro and more systemic levels:

- At the micro level: what is the potential for improving public-sector effectiveness by fostering problem-focused relationships of cooperation between staff within public bureaucracies and stakeholders outside government?

- At the systemic level: To what extent do gains in addressing micro-level problems – and associated gains in trust among the stakeholders involved – cascade beyond their immediate context and transform perceptions more broadly, thereby contributing to a broader renewal of the perceived legitimacy of the public domain?

The research papers introduced in this post explore the above questions. Two of the papers are largely conceptual (see here and here), and two are more empirically-oriented – a case study of the governance of affordable housing and homelessness in Los Angeles, and an interpretive exploration (co-authored with long-time civil society activist Mark Heywood and anchored in two sectoral case studies) of the evolving interface between civil society and the public sector in South Africa.

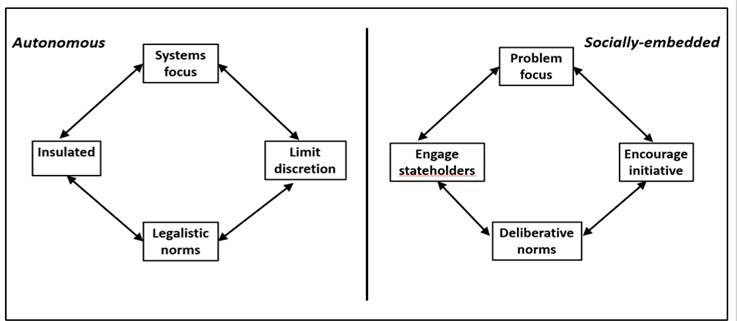

Figure 1 contrasts SEB with conventional notions of how public bureaucracies should be governed. In the conventional view, governance is organized hierarchically, with a focus on ‘getting the systems right’ Citizens engage upstream via their selection of political representatives who oversee both policymaking and implementation. The tasks of public officials are defined by legalistic, rule-bound processes, which also insulate public bureaucracy from political interference. Civil society’s governance role is to bring pressure from the demand-side to help ‘hold government to account’. By contrast, SEB is problem- rather than systems-oriented; it incorporates horizontal as well as hierarchical governance arrangements; interactions (both within the bureaucracy and at the interface with civil society) are less legalistic and more adaptive, oriented towards deliberation and fostering initiative.

Figure 1: Autonomous and socially-embedded bureaucracies

SEB’s distinctive characteristics create opportunities for improving public sector performance via three channels that are unavailable to insulated bureaucratic hierarchies:

- Fostering synergies – (problem-level) gains from co-operation between public bureaucracies and non-governmental actors;

- Clarifying goals – alliance-building among reform-oriented public officials and civil society actors as a way of bringing greater clarity to the (problem-level) goals to be pursued by public agencies.

- Streamlining monitoring – transforming the governance arrangements for (problem-level) monitoring and enforcement from a morass of red tape to trust-building interactions between public officials and service recipients.

Taken together, the above three channels have the potential to unleash human agency by opening up (problem-level) space for public/civic entrepreneurs to champion change. (See my ‘microfoundations’ paper, published by the Thinking and Working Politically Community of Practice for detailed exploration of each of the channels. And see the Los Angeles case study for an exploration of how these channels are at the center of efforts to more effectively address the twin crises of affordable housing and homelessness.)

Alongside recognizing its potential, a variety of concerns vis-à-vis SEB also need to be taken seriously. The first two are evident at the micro-level:

- The implications for public sector performance of a seeming inconsistency between SEB’s horizontal logic and the hierarchical logic of bureaucracies.

- The hazards of capture or vetocracy that might follow from opening up the public bureaucracy to participation by non-governmental stakeholders.

The third is a systemic level concern, namely that:

- Championing SEB as a way to renew the legitimacy of the public domain mis-specifies what are the underpinnings of social trust.

The paragraphs that follow consider each in turn.

To begin with the seeming tension between horizontal and hierarchical logics, the organizational literature on private organizations suggests that there is perhaps less inconsistency than it might seem on the surface. Viewed from the perspective of that literature, the challenge is the familiar one of reconciling innovation and mainstream organizational processes, and it has a clear answer: ‘shelter’ innovation from an organization’s mainstream business processes. As Clayton Christensen put it in The Innovator’s Dilemma:

Disruptive projects can thrive only within organizationally distinct units…When autonomous team members can work together in a dedicated way, they are free from organizational rhythms, habits

Consistent with Christensen’s dictum, the problem-specific building blocks of SEB potentially provide space for protagonists to work together flexibly, at arms-length from broader organizational rigidities.

The second set of concerns follows from SEB’s opening up of the public domain to participation by non-governmental stakeholders. At one extreme, an inadvertent consequence of opening up might be a ‘vetocracy’, with enhanced participation providing new mechanisms through which status-quo-oriented stakeholders can stymie any efforts at public action. At the other extreme, openness might inadvertently facilitate capture by influential non-governmental insiders. As the microfoundations paper explores, these hazards potentially can be mitigated via a combination of vigorous efforts to foster a commitment among stakeholders to clear, unambiguous and measurable shared goals – plus a complementary commitment to open and transparent processes. These commitments can build confidence in what is being done, while also reducing the pressure for control via heavy-handed, top-down systems of process compliance.

The third (systemic-level) concern interrogates the presumption that SEB can help to transform more broadly civic perceptions as to the legitimacy of the public domain. As my second TWP paper explores, a variety of eminent scholars (including Sam Bowles and Margaret Levi) have argued that initiatives that seek to renew the public domain by building working-level relationships between civil society and public bureaucracy mis-specify what it takes to improve social trust. Social trust, they argue, rests more on the quality of institutional arrangements and commitment to universal norms than on the relational quality of the government-society interface. This argument is eminently plausible in contexts where background political institutions are strong and stable. But, as the TWP papers explore, in contexts where disillusion and institutional decay have taken hold, renewal of the public domain – and thus confidence in the possibility of achieving collective gains through social cooperation – requires more than yet another round of institutional engineering.

There are, to be sure, many ways to foster ‘pro-sociality’ that are not linked to SEB-style initiatives at the interface between public officials and non-governmental actors. These include strengthening of trade unions and other solidaristic organizations within civil society, and intensified efforts to foster economic inclusion in contexts characterized by high and rising economic inequality. Even so, as examples from Los Angeles, South Africa and the USA illustrate, the systemic potential of SEB should not be dismissed out of hand.

Especially striking in Los Angeles has been the repeated willingness of voters to support ballot initiatives in which they tax themselves to finance homelessness services and the construction of affordable housing. However, as declining majorities for these initiatives signal, patience is wearing thin. The SEB-like governance reforms on which the LA case study focuses are intended to help renew civic commitment via transparent and participatory processes of goal-setting and accountability; how this is playing out in practice is my current research focus.

Turning to South Africa, my recent paper with long-time civil society activist Mark Heywood explored some interactions between civil society strategies and state capacity over the quarter century since the country made its extraordinary transition to constitutional democracy. Civil society’s principal strategy of engagement has been adversarial. This adversarial approach yielded major victories, including the reversal of AIDS-denialism in government, and momentum for a successful push-back against state capture. Over time, however, a series of political drivers (explored here and here) resulted in a weakening of state capacity. In parallel, civil society’s wins through adversarialism became fewer, and the effect on citizen disillusion became correspondingly corrosive. The Heywood-Levy paper thus makes a case for civil society to complement confrontational strategies with approaches centered around building problem-level coalitions with those public officials who remain committed to a vision of service. (The paper is slated to be part of a forthcoming edited volume by MISTRA; in the interim, interested readers can feel free to email me to request a PDF.)

Finally, opening the aperture even further, Robert Putnam’s 2020 book, The Upswing, raises the possibility that SEB might usefully be part of a strategy for renewing civic perceptions of the legitimacy of the public domain, a way for forward-looking leaders to champion an electoral and governance platform centred around a vision of partnership between the public sector and non-governmental actors. Political and social mobilization centered around deliberative problem-solving would be a radical departure from contemporary pressure-cooker discourses which thrive on raising rather than reducing the temperature. But, as Putnam explored, it happened in the USA between the 1880s and the 1920s, and it might happen again:

A distinct feature of the Progressive Era was the translation of outrage and moral awakening into active citizenship… to reclaim individuals’ agency and reinvigorate democratic citizenship as the only reliable antidotes to overwhelming anxiety……[Similarly], our current problems are mutually reinforcing. Rather than siloed reform efforts, an upswing will require ‘immense collaboration’, [leveraging] the latent power of collective action not just to protest, but to rebuild.”