In early February, I wrote a blog post that laid out some lessons for today’s USA’s from South Africa’s efforts to protect the guardrails of democracy. Here is a link to the piece. A hundred days into the Trump administration, how well does the piece stand the test of time? While the four lessons it highlighted (see the end of this post for a summary…..) remain reasonably on target, for at least three reasons South Africa’s experience turns out to be a more imperfect lens for understanding how to meet the challenges of sustaining democracy in the face of hostile actors than I realized at the time of writing.

First is a fundamental difference between South Africa’s early 1990s struggles to stay on a democratic path and those of the contemporary USA. In South Africa, those in control of the state (FW de Klerk’s National Party), while hesitant, wanted to go down the path of democratic constitutional reform. By contrast, in early 2025 USA, the levers of government seem unequivocally in the hands of those who have demonstrated no commitment to a constitutional democratic order.

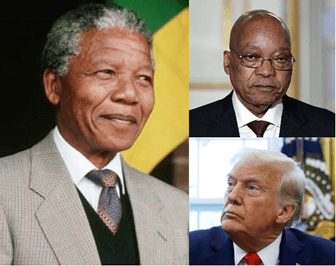

Second, while top-down cronyism aptly describes at least part of Jacob Zuma’s South Africa, and Donald Trump’s USA, its consequences depend in important part on the character and commitment of the leaders. I won’t try to parse which of the two is more corrupt. But what does seem clear is that Jacob Zuma – whose life had been shaped by the African National Congress and its struggle against apartheid (including ten years’ imprisonment with Nelson Mandela on Robben Island) – was committed in at least some part of his identity to the ANC’s aspirations and values. These values included longstanding, deeply-rooted commitments to democracy, to non-racialism, and to the rule of law. These commitments required Zuma to at least think twice before acting in ways that were directly contrary to these values. Donald Trump shows no evidence of any similar commitment and associated restraint.

Third is the relentless ideological zeal of at least parts of the Trump administration. An anti-government discourse has long been part of the Republican Party’s DNA. Even so, I have been startled by the (Musk-ian) recklessness with which agencies have been dismantled, heedless of consequences in the real world. Delving further into the ideological pedigree of the ideas held by another part of Trump’s unwieldy (but unfailingly loyal) coalition has left me feeling even more shaken and (a little) vulnerable.

Beneath the sometimes genteel language of political philosophy is the stuff of nightmares. To illustrate, here is a quote from Patrick Deneen (whose intellectual pedigree passes through Princeton, Georgetown, and currently the University of Notre Dame, and who both JD Vance and Pete Hegseth have found inspirational):

“What is needed, in short, is regime change – the peaceful but vigorous overthrow of a corrupt and corrupting liberal ruling class and the creation of a postliberal order…..Where necessary, those who currently occupy positions of economic, cultural and political power must be constrained and disciplined by the assertion of popular power…… The power sought is not merely to balance the current elite, but to replace it…..The aim should not be a form of ‘democratic pluralism’ that imagines a successful regime comprised of checks and balances, but rather the creation of a new elite that is aligned with the values and needs of ordinary working people”.

For those of us who know history’s catastrophes deep in our bones, these words are chilling. Perhaps the one silver lining is that, as of this time of writing, the agenda has been laid bare, its execution has been chaotic, and it is (perhaps) being stopped in its tracks by increasingly mobilized resistance. So, as with so much of my work these days, I’ll end by taking inspiration from Albert Hirschman’s bias for hope – in this instance the hope that, as per the first lesson of the February post, American democracy can indeed make it intact to the November 2026 mid-term elections.

*****

Here are the four “lessons from South Africa” laid out in the February piece:

Lesson #1: For the next 21 months, the unwavering navigational north star is to get to the November, 2026 midterms with the machinery of electoral democracy still fully functional – avoid being knocked off course by even the most venal provocations.

Lesson #2: Leveraging checks and balances lays important, necessary ground for victory in the struggle against tyranny – but its victories are not in themselves decisive.

Lesson #3: Keeping democratic space open requires a coalition that is broader than the usual fault lines of political partisanship – a sense of urgency and willingness to act not only from ‘natural’ opponents but from elite actors for whom it is more expedient to stay silent.

Lesson #4: A vision of democratic renewal is key to a decisive victory against encroaching tyranny – more than short- and medium-term band aids are needed.