(Part of a series)

What will it take to break the downward spiral of polarization in which we seem trapped? In their best-selling book, Abundance, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson offer their answer, wielding ideas as their weapon of choice.

For ideas to be truly transformative, they need to do more than persuade intellectually, they need also to connect viscerally – both in their resonance with the prevailing discourse, and in the energy they evoke among their potential champions. Abundance has been written with that transformative intent. The book offers both a wake-up call and a positive vision. But it largely is silent vis-à- third task, one that is key to inspiring a sense of hope, of possibility – it does very little to translate its positive vision into a practical, positive agenda for action. The result has been that instead of serving as an invitation to progressives to loosen the grip of conventional ways of doing things and embark on a new quest Abundance has become yet another source of polarized political combat.

The blog series introduced here endeavors to fill the gap – its principal focus is how to get from here to there. A companion post (see here) lays out an approach for moving from vision to action centered around building problem-focused coalitions among reform-minded public officials and non-governmental actors. The third and fourth posts provide empirical illustrations of the approach (both potential and challenges). The third post explores some interactions between civil society and the public sector in democratic South Africa. The fourth post (forthcoming in January) will be a stocktaking and update of Los Angeles’ efforts to address homelessness in the face of a a worsening fiscal crisis. (See here for some of my recent research on both LA’s crisis and recent governance reforms aimed at addressing it.) This post sets the stage, by locating the exploration within Klein & Thompson’s broader vision of the interaction between governance and political orders.

Drawing on the work of Gary Gerstle, Klein & Thompson define a political order as: “a ‘constellation of ideologies, policies and constituencies…..that endures beyond [individual] election cycles”. Political orders don’t change simply via the promulgation of new policies or even electoral alternation. Rather: “policy is downstream of values……What is needed is a change in political culture, not just a change in legislation …..New ideas give way to new laws, new arguments and new customs. People working at all levels of society, inside and outside government, bring these ideas into their labors….”. As Gerstle puts it: “For a political order to triumph, it must have a narrative, a story it tells about the good life”.

A story about the good life has been central to both of the political orders that shaped American politics over the past century: the New Deal order (roughly 1933 to1979) offered a vision of middle-class prosperity; its vision ran aground in the face of social conflict in the 1960s, and stagflation in the 1970s. The neoliberal political order (roughly 1980-2015) followed; it was centered around a vision of abundance fueled by unleashing the power of private entrepreneurship and the capitalist marketplace. But by the mid-2010s, it also had reached its sell-by date – undermined by a combination of rising inequality, financial crisis, political polarization, and (in the wake of the election of Barack Obama) resurgent racism.

Klein & Thompson argue that at least since Donald Trump’s first electoral victory in 2016 we have been living in “A messy interregnum between political orders; a molten moment when old institutions are failing, traditional elites are flailing, and the public is casting about for a politics that feels like it is of today rather than yesterday.“ Abundance’s implicit goal is nothing less than to offer some foundational ideas for a next-generation renewal of a progressive political order.

As per its title, the book’s narrative about the good life’ is one of……….abundance….. but framed from a progressive perspective. Conventionally, the pathway to abundance is via the market – and the abundance that is offered is the familiar consumer cornucopia. Abundance offers something different: “We have a startling abundance of the goods that fill a house, and a shortage of what’s needed to build a good life……… Housing. Transportation. Energy. Health. Abundance is the promise of not just more, but more of what matters….It is a determination to align our collective genius with the needs of both the planet and each other…..“

Addressing the shortages calls not only for the entrepreneurial flair of private, for-profit business, but also for the effective provision of public goods – and thus for a capable state. But how to achieve the latter? As their (indirect) answer to this question, Klein & Thompson offer a wake-up call.

Alongside its positive vision, Abundance lays out a relentless “….critique of the ways that liberals have governed and thought over the past fifty years”. (p. 211) Klein and Thompson argue that two deeply-held progressive nostrums stand in the way of achieving abundance. There is an ‘everything bagel’ approach to governance: “At every level where liberals govern….they often add too many goals to a single project. A government that tries to accomplish too much all at once often ends up accomplishing nothing at all……Many of the goals are good goals. But are they good goals to include in [this] project? ….with no discussion of trade-offs….or any admission that anything asked for even represented a trade-off”.

And there is a pre-occupation with formal process, fueled by a hyper-sensitivity to the hazard that government will all-too-easily be captured by powerful special interests. In consequence: “Liberal legalism – and through it, liberal government – has become process-obsessed rather than outcomes oriented. It had convinced itself that the state’s legitimacy would be earned through compliance with an endless catalog of rules and restraints rather than through getting things done for the people it claimed to serve.” (pp. 90-91)

Both critiques are underpinned with a wealth of damning examples ranging from the morass of regulatory obstacles to expanding the supply of affordable housing, to hyper-cautious constraints on the financing of scientific innovation; and to the disaster of a California high speed rail project that was approved in 2008, spent close to $15 billion over the subsequent seventeen years, but has not yet laid any high speed rail track.

Beyond the very general assertion that “to pursue abundance is to pursue institutional renewal”, Klein &Thompson’s discussion of governance is framed almost entirely as a critique. They largely are silent vis-à-vis the question posed at the beginning of this blog post – how to translate their positive vision into a practical, positive agenda for action?

In his recent book, Why Nothing Works, Greg Dunkelman suggests a way to close the gap between vision and action that aligns closely with Klein & Thompson’s analysis. He frames the issue as a tension between Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian approaches to governance: “When progressives perceive a challenge through the Hamiltonian lens, the movement tends to embrace solutions that will pull power up and in. When, by contrast, a problem appears born of some nefarious centralized authority, the movement argues for pushing power down and out……our (contemporary) aversion to power renders government incompetent, and incompetent government undermines progressivism’s political appeal.”

A seemingly obvious conclusion follows: getting things done means becoming less Jeffersonian, and more Hamiltonian – to become more willing to use top-down power to get things done. A corollary follows: stop weighing projects down with too many goals and too many processes.

But Dunkelman’s prescription is accompanied by two large vulnerabilities of its own. The first is highlighted in a question recently posed by Francis Fukuyama: Recognizing that the formal rules of American democracy by themselves are inadequate to create a healthy democracy, how do we design new participatory institutions that are compatible with getting things done? A companion post explores in detail a variety of possible answers to this question. The second vulnerability is one that practitioners who have spent decades wrestling with the challenge of integrating governance reform and practical strategies for improving peoples’ lives know all-too-well – the argument that to change anything one must change everything. Argumentation along these lines has proven to be a recipe for hubris, disappointment, and subsequent cynicism.

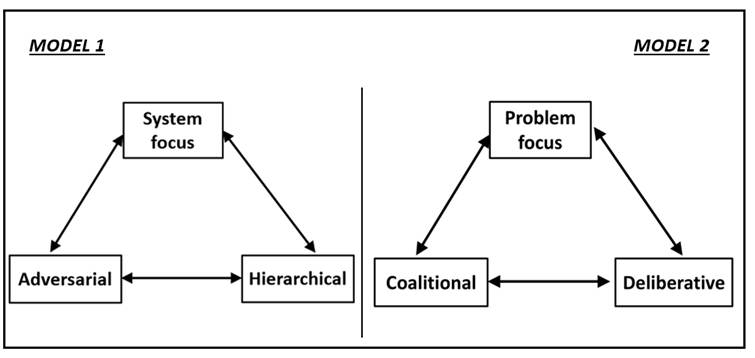

Gradually, after repeated cycles of high ambition and dashed hopes, a hard-won lesson in humility has been learned. Gains on the ground generally cumulatively, step-by-step – achieved even in the midst of broader political and institutional messiness. As the second post in this series explores, three mutually-reinforcing guideposts seem key to success: focus on problems rather than systems; champion deliberative, rather than hierarchical/ legalistic bureaucratic norms; foster coalition building that brings together non-governmental actors and those within the public bureaucracy committed to realizing the public purpose. (Case studies in posts three and four explore some practical implications – both opportunities and challenges – of applying these guideposts.)

Here, to preview, is the overarching message of this series: Transformational change does not require fixing everything, everywhere, all at once. On the contrary, as subsequent posts will explore, bringing attention to the practical can inspire – through its focus on concrete gains, its evocation of human agency and, more broadly, in the power that comes from cultivating shared (problem-level) purpose to actually get things done.

Taking the workaday seriously does not detract from Abundance’s vision. It aligns with it – and, in its practicality, enhances its potency. Indeed, as per Klein & Thompson’s vision of a transformed political order, as subsequent posts in this series explore (and as I analyze in depth in an article for the Thinking and Working Politically Community of Practice), perhaps focusing activism around “the goods needed to build a good life” has the potential to set in motion a new kind of social movement, one centered around a vision of deliberative, problem-focused partnerships between the public sector and non-governmental actors – a social movement fueled not by polarizing rage but by practical, inclusive hope.