Now what? Four weeks into the Trump administration, a wrecking ball threatens to wreak havoc with millions of peoples’ lives. A sense of urgency is in the air. Indeed, we urgently need to bear witness to the emerging scale of disaster. But holding open the door to a hopeful future needs more than urgency. It needs clarity of goals, tactics and strategy – plus a longer-term vision that looks beyond the immediate crisis. To help bring clarity, it can be helpful to make comparisons.

In seeking to understand America’s challenges, I have long looked to South Africa’s decades-long struggle to establish and sustain its own democracy. A recent effort contrasted how polarization and inequality interacted. My task here is the more immediate one of seeking fresh insight into how a democracy can respond to a wrecking ball taking aim at its institutions. The search yielded four lessons of relevance to America’s current moment. First:

- For the next 21 months, the unwavering navigational north star is to get to the November, 2026 midterms with the machinery of electoral democracy still fully functional – avoid being knocked off course by even the most venal provocations.

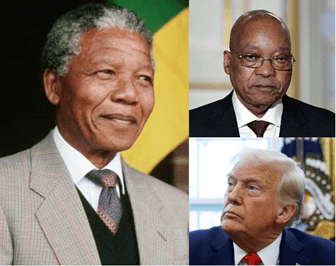

In April 1993, a team of far-right assassins that included a former member of the white apartheid parliament murdered Chris Hani, a popular, senior leader of the ANC’s left-wing. At the time, South Africa’s recently unbanned African National Congress was in the midst of fraught, on-and-off negotiations to end apartheid – but until a new constitution could be agreed on, power remained in the hands of the apartheid-era National Party. When news of the assassination broke, the country erupted in rage; the stage was set for crackdown. Instead, in a masterful display of statesmanship, Nelson Mandela went on national television and successfully redirected attention to the journey ahead. The country’s first democratic elections, held in April 1994, resulted in a massive ANC victory, with Mandela sworn in as national president.

Decades after its inspiring transition from apartheid to democracy, South Africa confronted a new challenge to its constitutional order – and again demonstrated the centrality of the electoral process to its defense. Jacob Zuma, the ANC leader who acceded to the presidency in 2009, was increasingly using state power in personalized and often corrupt ways, under the guise of a populist anti-elite agenda. Given the ANC’s continuing electoral dominance, defeating Zuma’s successor in a national election (Zuma himself was term-limited….) was not a plausible strategy. In selecting a successor, the ANC itself had to decide whether to re-embrace the democratic constitutional order. This it did. Cyril Ramaphosa, a central protagonist in the crafting of the constitution in the 1990s, won the November 2017 (intra-party) electoral contest to become Zuma’s successor by a hairs-breadth – and then decisively won the 2019 national elections. Ramaphosa’s victory not only underscores the centrality of elections in pushing back against tyranny, how he won underscores the relevance of the second and third lessons.

The second lesson is largely familiar:

- Leveraging checks and balances lays important, necessary ground for victory in the struggle against tyranny – but its victories are not in themselves decisive.

In the 2010s, South Africa’s defenders of democracy brilliantly used checks and balances institutions to push back against state capture. The pushback included brave, determined inquiry from the ‘Public Protector’, an official, but arms-length agency with a mandate to investigate abuse of power; investigative journalism, underpinned by university-based researchers whose efforts added to the credibility of efforts to document what was happening; and a high-profile public inquiry led by the Deputy Chief Justice of the country’s supreme court. Four weeks into the Trump administration, similar momentum is building in the United States. The courts are intervening; elected Democrats in the House and Senate are becoming increasingly emboldened and forceful in mobilizing resistance; citizens are spontaneously coming out in support. But experience in South Africa and elsewhere shows that more is needed.

The result of a too-narrow pre-occupation with tactical victories can all-too-easily be to win many battles, but lose the broader war. Hence the third lesson:

- Keeping democratic space open requires a coalition that is broader than the usual fault lines of political partisanship – a sense of urgency and willingness to act not only from ‘natural’ opponents but from elite actors for whom it is more expedient to stay silent.

It takes courage to override expediency and party loyalty and lead with principle. In 1930s Germany, expedient silence (indeed, often, tacit support) on the center-right opened the door for Adolf Hitler, and all that followed. 2010s South Africa, by contrast, saw some inspiring examples of courage. Veteran leaders of the ANC (including Pravin Gordhan; Ahmed Kathrada; and Mavuso Msimang to name just a few) were willing to override lifetimes of loyalty and take a high-profile principled stand against state capture in favor of constitutional democracy. In the USA, principled Republican leaders who took a stand against Richard Nixon in the early 1970s showed similar courage. But in today’s United States, aside from a few lonely voices, the silence from the center-right is deafening.

The combination of a multi-front effort to leverage checks and balances institutions and mobilization of a broad coalition may be enough to eke out an electoral victory – but it has not been enough to decisively turn the tide. Both the 2019 South African and 2020 U.S., elections enabled a temporary pause in attacks on constitutionalism. But more than a pause was needed. Hence the fourth lesson:

- A vision of democratic renewal is key to a decisive victory against encroaching tyranny – more than short- and medium-term band aids are needed.

On offer in South Africa’s 1990s “rainbow miracle” was not only formal constitutional change, but hope – “a better life for all” as per the African National Congress’s campaign slogan. Indeed, after decades of stagnation, the first fifteen years of democracy witnessed a steady acceleration of economic growth, and a reduction in the incidence of extreme poverty. But by the time Zuma acceded to the presidency, the promise had reached its sell-by date. Ramaphosa promised only a return to the earlier formula, and his presidency has turned out to be a time of muddling through. Viewed from the vantage point of 2025, parallels with the Biden presidency are clear.

For an electoral victory to result in a decisive political realignment, it needs to build credibility on two fronts – inclusion, and public governance. South Africa’s early successes centered around an expansive “we” – underpinned by an economic program that addressed many everyday concerns of working people. In the wake of 2024’s electoral shock, the Democratic Party in the U.S. seems increasingly to be learning the lesson that the cobbling together of multiple disparate parts does not add up to an expansion vision of ‘inclusion’. To win credibility with the electorate the message needs both sharpening and consistent championing by credible messengers.

As for the capacity to govern, a distinctively American challenge is to break through the relentless drumbeat of political demonizing of the public sector. But the challenge goes well beyond messaging. All-too-often, the result of a progressive vision of governance in which one good thing is added on top of another is way less than the sum of its parts – each good thing is accompanied by a small dose of administrative process, and the cumulative sum of the good things is sclerosis. The Wall Street Journal’s Peggy Noonan makes the point pithily:

“A word to Democrats trying to figure out how to save their party…. Most of all, make something work. You run nearly every great city in the nation. Make one work—clean it up, control crime, smash corruption, educate the kids. You want everyone in the country to know who you are? Save a city.”

In 1860 when Abraham Lincoln became president, he described America as “the world’s last best hope”. That is how it felt to me when I came to this country almost five decades ago. Is the vision of America as a beacon to the world coming to an end? Is there no alternative to angry, chauvinist isolationism? Making it through the present moment without deepening disaster requires tactical resistance – but it also calls for more. We also need to raise our sights. What kind of country do we want the United States of America to be?