I’ve lived through this before. My first two decades of life were during peak apartheid in Cape Town, South Africa. Beneath the glistening surface of the city’s sunshine, mountains and ocean was tyranny. Police cars roamed the street, looking to immediately deport black people who didn’t have the required ‘dompas’ document. Families were forcibly removed from their homes. Informal settlements were bulldozed. Brutalization coarsened life -not only for those who were direct targets, but for everyone.

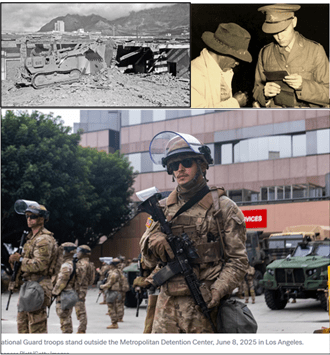

When I came to the United States in the late 1970s, it was with a sense of relief, hope and possibility – now I was living in a land dedicated to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”, a country that promised, in words engraved above the main entrance to the Supreme Court building, “equal justice before the law”. And when I moved to Los Angeles about three years ago, I was thrilled to discover a city that, contrary to East Coast stereotypes, was vibrant, welcoming, and rich in its cultural diversity. Yet in the days since the Trump administration unleashed Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and federal troops on the city I have lain awake at night, shocked and distressed by the parallels between my early years in Cape Town and what is happening in LA.

As someone committed to exploring how history shapes culture, politics and the economy I am mindful of the many differences between LA and Cape Town, and their implications for policy choices. But in what follows my primary purpose is not to explore nuance, but to assemble some baseline data (taken, except where noted, from a 2024 California-wide study, centered around 2019 data) in a way that directs attention to two urgent issues: (i) the catastrophic social and economic consequences for LA if the Trump administration continues to pursue its militarized and rhetorically shrill and polarizing approach to forced removals; and thus (ii) the urgency of crafting a different way forward. I organize the data around five sets of stubborn facts.

Stubborn Facts I: Undocumented residents comprise a significant share of of LA’s – and California’s – population.

- Undocumented residents account for 9.5% of Los Angeles County’s population of about 10 million people; another 20-25% of LA County’s population is foreign born.

- About 20 percent of LA County residents live in a household where at least one person is undocumented.

- Across California, 2.8 million of the state’s total (2019) population of 39 million was undocumented.

Stubborn Facts II: Undocumented residents are deeply embedded into Californian society.

- 31% of California’s 2019 undocumented population had been resident in the state for 20 or more years; 41% for 10-19 years; 13% for 5-9 years; and 15% for less than five years.

- More than half of the undocumented population live in households that include a citizen or permanent resident.

- 20% of all children under age 18 in LA County (and 17% across California) live in a household where at least one person is undocumented.

Stubborn Facts III: The assault on undocumented residents targets especially the state and county’s Latino population

- 48% of the population of LA County – and 39% of all Californians – are Latino.

- 86% of California’s total Latino population of 15.2 million people are citizens or permanent residents.

- As of 2019, about 75% of California’s undocumented population was Latino; almost 1.7 million people came from Mexico, and a further 360,000 from El Salvador and Guatemala. An additional 2.3 million Latino citizens of California live in a household where at least one person is undocumented; 4 million people will thus be directly affected by mass deportations.

- Across California, 29% of Latino children live in a household where at least one person is undocumented.

Undocumented residents are intertwined with California’s long-established Latino community – a community that cuts across classes, and localities. In the vibrant, culturally-diverse Los Angeles County, whose Latino residents are neighbors, friends, and co-workers, targeting the undocumented Latino population for forced removal will be devastating – not only for those immediately affected, but for all of us.

Stubborn Facts IV: Undocumented residents are woven deep into the economic fabric of Los Angeles.

- As of 2019, over 64% of all California’s undocumented residents above the age of sixteen were employed (as compared with 59% for the working age population as a whole); less than 5 percent were unemployed.

- Median 2019 hourly wages across California were $13 per for undocumented workers, $19 for immigrants and $26 for the US-born population

- Across California, 52 percent of undocumented residents have less than a high school education; 22% have a high school diploma; and 26% have at least some college education.

- Across California, undocumented workers account for approximately half of all employment in agriculture – and a similar percentage of child care, home aide, housecleaning and other domestic workers.

- In LA County, undocumented workers account for about a third of all construction sector employment, 21% of manufacturing employment, and 17-20% of employment in hospitality, wholesale and retail trades.

Forced removal of undocumented workers will thus have devastating consequences for labor supply at the less skilled end of the labor market, with widespread bankruptcies and cost escalations likely in multiple sectors.

****

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes. South Africa’s forced removals began in the late 1940s. They set in motion a cascading cycle of decade-long protest, two decades of brutal repression and dehumanization – and then mass civic uprising. Sustained efforts at forced removals in LA will almost surely be accompanied by a parallel combination of protest and repression – a massive blow to the heart of a great city.

How to avoid catastrophe? To address this question, we need to add a fifth set of stubborn facts to the four laid out above. Between 1970 and 2024, the share of the American population that was foreign born rose from 4.7% to 15.6%, with the latter the highest percentage since at least 1850. In the four years of the Biden administration the estimated number of undocumented people living in the United States rose by over 5 million. If catastrophe is to be avoided, simply ignoring the structural underpinnings of America’s current anti-immigrant fervor is not an option.

But nor is it an option to ignore the far-reaching social and economic consequences of the draconian imposition of immigration policy. The bloodless technocratic advocacy of ‘robust’ enforcement of existing policies (for example, this New York Times podcast conversation between right-of-center columnist Ross Douthat and the American Enterprise Institute’s Matthew Continetti) is as outrageously detached from any realistic reckoning with consequences as reckless, twitter-fueled pyromania.

It has been clear for decades where a constructive path might be found – through the hard work of legislative reform. But instead of reform, contestation over immigration policy has become Exhibit Number One of a broken political system. Back in 1986, Republican-championed immigration reforms, signed into law by then president Ronald Reagan, provided a path to citizenship for undocumented migrants who had lived and worked in the USA for at least five years. By contrast, a 2024 effort at legislative compromise offered a path to permanent residence and citizenship only for undocumented residents who both were married to US citizens, and had been in the USA for at least ten years – an astonishingly inadequate proposal when viewed through an LA lens. Even so, it was the opposition of then presidential candidate Donald Trump, not Democratic opposition, that ended the reform effort.)

But the parallel with South Africa does not only provide a cautionary tale of how things could go wrong; it also points to the possibility of something radically different. The country’s extraordinary ‘rainbow miracle’ transition to democracy shows that, even for conflicts that seemingly are intractable, a collective commitment to finding a way forward can yield transformational positive change. Has the USA become so incapable of collective, problem-solving deliberation that (to paraphrase the eighteenth century philosopher Samuel Johnon) even the threat of a hanging cannot focus our minds?

Brian, this is very good and very useful to everyone. But it would be even better if you offered some suggested routes through these facts. I sincerely hope that these may still be coming – no doubt Working with the Grain as necessary. Warm wishes, Gerry Helleiner