(part of a series)

Increasingly, we seem trapped in an accelerating downward spiral of polarization, with no way out. What will it take to break the spell? In their best-selling book, Abundance, Ezra Klein & Derek Thompson seek to answer the question by leading with ideas. They lay out a compelling positive vision, accompanied by a stark wake-up call. However, they say little about how to translate their positive vision into a practical agenda for action. The resulting gap leaves the field open for their critics to presume the worst.

This post, the lead in a series that aims to build on Abundance’s hope-evoking foundation, lays out an approach for filling the vision-to-action gap. Subsequent posts use case studies to explore how the approach introduced here plays out in practice – both the successes that have been achieved, and challenges that have arisen. But before before getting into the details of the journey from vision to action, it is helpful to briefly recapitulate Abundance’s core argument (See this preliminary stage-setting post for a more comprehensive treatment.)

In the usual political discourse, the pathway to abundance is via the market – and the abundance that is offered is the familiar consumer cornucopia. Klein & Thompson, by contrast, offer a vision “not just of more, but more of what matters ” More housing. Better public transportation. Clean, affordable energy. And a health system that works for everyone.Achieving these requires not only private entrepreneurship but also a capable state. Thus, Klein & Thompson suggest, “to pursue abundance is to pursue institutional renewal,” However, they say very little about what this implies in practice, and offer instead a relentless critique of how progressive governance is prone to an excess of (performative) responsiveness, with well-meaning initiatives becoming overloaded with too-many goals and too-many checks on decision-making.

As Greg Dunkelman elaborates in his book Why Nothing Works, the seemingly obvious way to close the gap between vision and action is to become more willing to use top-down power to get things done. A greater willingness to act is indeed part of what is needed. But a call for bold top-down institutional renewal can also become a trap – the argument that to change anything one must change everything.

Practitioners who have spent decades wrestling with the challenge of integrating governance reform and practical strategies for improving peoples’ lives have learned the hard way that “best practice” argumentation along these lines can all-too-often be a recipe for hubris, disappointment, and subsequent cynicism. Gradually, after repeated cycles of high ambition and dashed hopes, a hard-won lesson in humility and practicality has taken hold. Gains can be achieved even in the midst of broader governance and political messiness – not in one fell swoop, but cumulatively.

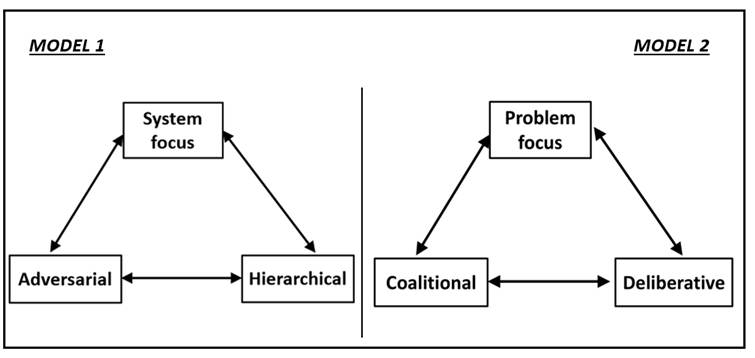

The figure below encapsulates what has been learned in the form of two contrasting ‘models’ for fostering results-focused renewal of government – a top-down, plan-then-implement ‘engineering’ model, and a model centered around iterative social learning in the midst of uncertainty. (See here for an in depth technical presentation of the approach, and its provenance in the public management literature.) As the paragraphs that follow detail, the ‘models’ vary radically from one another in their answers to two fundamental questions: “What” should be the focus of the reform effort? “How” should reform should be pursued? Each question is considered in turn.

The difference between the two models in the ‘what’ of reform is captured in the top boxes in the figure – systems-reform versus reform that focuses on the problem-level. Improving ‘systems’ – the institutional architecture of government – is a worthy endeavor, but it yields results on the ground only over the medium term. Especially when the broader political and institutional context is messy (as it is in most places, most of the time), reforms that aim to systematically reshuffle the bureaucratic deck can all too easily get lost in bureaucratic minutiae and end up achieving nothing.

By contrast, a problem-focus provides a compelling focal point for results-oriented action. As per its champions, it offers “…..a ‘true north’ definition of ‘problem solved’ to guide, motivate and inspire action…. A good problem cannot be ignored, and matters to key change agents; can be broken down into easily-addressed causal elements; allows real, sequenced strategic responses.” (Note that Abundance’s focus on housing, transportation, energy and health – on “the goods needed to build a good life” – lends itself naturally to a problem-focused approach to reform.)

Turning to the ‘how’ of reform, a useful point of departure for surfacing differences between the two models is a question posed by Francis Fukuyama in a recent piece on the practical potential of Abundance. While Fukuyama is sympathetic both to the ideas in Abundance and to Dunkelman’s call for more top-down governance, he points to a troubling dilemma for democratic decision-making that follows from the prescription: “Public participation is one of the thorniest issues with which modern democracies need to deal…..Public input to democratic decision-making is absolutely necessary….It has been a long time since anyone believed that the formal rules of American democracy by themselves are adequate to create a healthy democracy……But how do we design new participatory institutions to meet the conditions [….needed to get things done]? Model 1 and model 2 offer very different answers to Fukuyama’s question.

In model 1, participation plays a role on the margin, an add-on of sorts to its top-down approach to getting things done. This add-on can take one or all of a variety of forms:

- Enhancing accountability for performance via a variety of formal checks and balances plus a range of less formal demand-side mechanisms (for example, advocacy/protest and investigative journalism).

- Championing transparency as a way to support arms-length efforts at monitoring and enforcement.

- Deliberative democracy – structured, time-bound mechanisms for eliciting input from citizens (see here and here).

Note the arms-length (and sometimes adversarial) relationship between the public sector and non-governmental actors that underlies each of these. As the case study of South Africa in the third blog post in this series suggests, when underlying state capacity is strong arms-length and adversarial approaches can be effective in improving performance; but they can be counterproductive when capacity is less and citizens have become increasingly disillusioned and cynical.

Model 2’s approach to participation is very different. The model brings non-governmental actors to center stage, not as adversaries or point-in-time deliberators, but as coalitional allies in the co-production of social value. As the figure signals, this differs from model 1 in two far-reaching ways – in how stakeholders engage with power, and in how they interact with one another.

To begin with power, model 1 presumes that space for reform is won and lost electorally. By contrast, in model 2 problem-level coalition-building is key to opening up space for reform. Stakeholders with an interest in the problem at hand differ radically from one another in both their goals and in the power they can command. Some are unambiguously supportive of the social purpose associated with the coalitional endeavor. Others are predators who seek to capture for their own private purposes what the protagonists are seeking to build. Coalition-building offers a way to achieve gains via the construction of problem-focused alliances that are sufficiently strong to fend off predators who might have private and political reasons for undermining the initiatives.

Beyond the immediate task of opening up space for reform, model 2 also involves an ongoing shift in ways of doing things on the part of both civil actors and reformers within government. For civil society, a central challenge is to put aside, for at least some problems and some key junctures in the process of change, the allure of adversarialism and embrace a more collaborative mode of engagement with the public sector. Correspondingly, the task for the public sector is to shift, in at least in some domains of activity, from a legalistic to a deliberative mode of engagement – valuable both in itself and as key to working collaboratively with civil society. (The third blog post in this series explores the opportunities and challenges associated with making this shift, centered around a recent in-depth analysis of interactions between civil society and the public sector in democratic South Africa. The fourth post (forthcoming in January) will be a stocktaking and update of Los Angeles’ efforts to address homelessness in the face of a worsening fiscal crisis. (See here for some of my recent research on both LA’s crisis and recent governance reforms aimed at addressing it.)

In his award-winning 2022 comparative analysis of the performance of education systems in two Indian states, Making Bureaucracy Work. Akshay Mangla captures the essence of the difference between how legalistic/hierarchical and deliberative bureaucracies do things. As he puts it:

“Legalistic bureaucracy urges fidelity to administrative rules and procedures….The ideal-typical Weberian state motivates bureaucrats to set aside their private interests and advance the public good…by insulating bureaucrats from political pressures and instilling a commitment to rational-legal norms….Bureaucrats are judged for following rules and not for the consequences that emanate from their actions….”

By contrast: “Deliberative bureaucracy promotes flexibility and problem-solving….it induces a participatory dynamic that urges officials to negotiate policy problems through discussion and adjust their outlooks to shifting circumstances…. It is found to have made a decisive impact with respect to literacy and the quality of education policy… It enables state officials to undertake complex tasks, co-ordinate with society and adapt policies to local needs, yielding higher quality education services.”

As Mangla details using the example of basic education, legalistic bureaucracy is more effective in addressing logistical tasks (eg building schools); deliberative bureaucracy is better at addressing complex tasks that require ongoing adaptation (eg improving learning outcomes and multi-dimensional challenges such as reducing homelessness).

Embracing problem-focused coalitions rather than insulating government from civil society comes with risks: the risks of reproducing performative progressivism that inhibits action; the risks of capture. But risks can be managed and, as argued earlier, these risks need to be set against the hazards of hubris, stasis and disillusion – of bold-sounding reforms that lead nowhere. There is risk and opportunity in all directions. Both/and is the way forward.

In sum, stepping back from the details of the two models, transformational change does not require fixing everything, everywhere, all at once. On the contrary, bringing attention to the practical can inspire in its focus on concrete gains, in its evocation of human agency, and in the power that comes from cultivating shared (problem-level) purpose to actually get things done. Taking the workaday seriously does not detract from Abundance’s vision, it aligns with it – and, in its practicality, gives it greater potency.

Perhaps even more may be possible. In the spirit with which Klein & Thompson wrote Abundance (see the companion stage-setting post) might problem-level gains provide a platform for a broader transformation of the interface between citizens and public officials? Might forward-looking political leaders embrace an electoral and governance platform centred around a problem-focused vision of partnership between the public sector and non-governmental actors to deliver “more of what matters to build a good life”? This would, of course, be a radical departure from contemporary pressure-cooker discourses that thrive on raising rather than reducing the temperature. But, as Robert Putnam explored in his 2020 book The Upswing, it happened in the USA between the 1880s and the 1920s, and it could happen again:

A distinct feature of the Progressive Era was the translation of outrage and moral awakening into active citizenship …Progressive Era innovations were seeking to reclaim individuals’ agency and reinvigorate democratic citizenship as the only reliable antidotes to overwhelming anxiety… National leadership came after sustained, widespread citizen engagement….. A [new] upswing will require ‘immense collaboration’, [leveraging] the latent power of collective action not just to protest, but to rebuild.”